The Guild

leaning into transformation

2021 Annual Report

When The Guild launched in 2015 as Atlanta's first co-living company, we brought together social entrepreneurs, artists, and community organizers in a live/work environment. Our goal was to support the people doing the most critical work with both affordable housing as well as programming to support their leadership development and personal growth.

Since then, The Guild has evolved quite a bit. As we pulled back the layers on various intersecting inequities — from gentrification in a majority Black city like Atlanta, food apartheid, to redlining — we realized real estate development is at the heart of so much.

We then set out to build a different type of real estate paradigm, one that grappled with the root causes of these inequities. This work involves creating alternative real estate models, but also alternative business models. As we say at The Guild, the means are the ends — how we do something is as important as what we do. This report shares some of our processes that are driven by our values, and gives you a glimpse into what 2021 was like for us.

Contents

This report is a robust summary of all the work we did in 2021. For ease of navigation, you can click on the hyperlinks below to jump to any particular section.

Introduction to Our Collective

Our Approach to Community Design + Development

Updates from Our Pilot Community Ownership Project at 918 Dill Ave.

2021 was a year of transformation...

At both global and local levels, the pandemic continued to reveal fundamental flaws in our systems and institutions that exacerbated the already-intense strains on Black and Brown communities. The pandemic remains a wake-up call to develop and invest in a future that is more equitable, resilient and sustainable.

While new variants and surges emerged, millions of homes were snatched by private equity and other investors, and millions of people were pushed to the brink of eviction. Nationally, one in seven homes were purchased by investors, and in Atlanta investors bought one in four homes, a record share and more than in any other metro area in the US. The risk of displacement is accelerating in Atlanta, and our local and state policies are insufficient to meet the needs of working class people.

Yet, 2021 also demonstrated our ability to adapt, to challenge those systems and push for building alternatives. For The Guild, this has meant reexamining and evolving to our very mission: how can we actually "create spaces for social change" for Black and brown folks when the pressures of racial capitalism constantly threaten and destabilize the spaces that exist, while making it increasingly difficult to create new ones?

We may not end capitalism in our lifetime — if a global pandemic couldn't do it, what could — but we can disrupt it, expand our imagination and capacity for what else is possible, and begin building alternatives right where we are, today. This Annual Report gives a glimpse of our progress so far, and where we hope to continue to grow.

our staff

2021 was our first year of operating as a full-time staff, and saw us adjusting to the balance of making our lives and work... work well. We also welcomed a new colleague, bringing our team to five. Driven by our values of equity, solidarity, and collective stewardship, we began our

journey of transitioning into a worker-owned cooperative.

Why we chose to be a

worker-owned cooperative

A worker cooperative is a values-driven business that puts worker and community benefit at the core of its purpose.

The main features of worker cooperatives are that workers own the business. as opposed to just management or investors. And they participate in and benefit from its financial success on the basis of their labor contribution to the cooperative. Worker-owned cooperatives also adhere to the principle of one worker, one vote

As we sought to build community-owned models for real estate, it was equally important for us to live into those democratic values within our company.

When each worker (member) shares in the ownership, where there is democratic participation in decision-making, and when we move in solidarity as workers in navigating the highs and lows of operating the business, there is a greater sense of unity, ownership and commitment. Investing the time and energy to achieve consensus on critical or urgent decisions, adapting the way we communicate and practice accountability as a collective, and overcoming our reflexes from traditional, hierarchical workplace structures are just

a few of the ways we continue to grow and evolve.

What propels us forward are our collective values. We understand that to partner well with and support communities in their journey to shared ownership and collective governance of local assets, it's important for us to live into those same values at an organizational level too.

AVERY EBRON (he/him)

Head of Community Product & Operations

DANI Brockington (she/her)

Community Engagement and Programs Manager

ANTARIKSH TANDON (he/him)

Development and Design Director

ZACHARY MURRAY (he/him)

Organizing & Movement Building Director

NIKISHKA IYENGAR (she/her)

Founder & Ecosystem Director

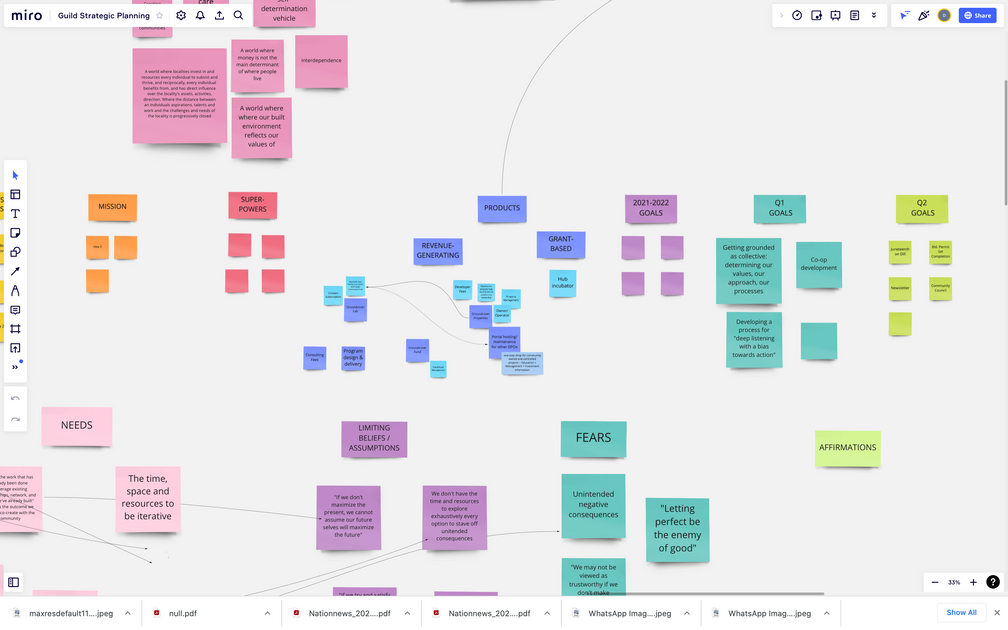

Getting grounded as a collective

The rollout of vaccines brought a lot of hope, if only for a brief period. During the summer, we were able to get together for an in-person team retreat where we coalesced around shared values and good food for a few days in Pineview, Georgia. Being on land with history of violence toward Black and Indigenous people, and a history of extractive agriculture and violence to our natural world — that is now a regenerative farm with plans to be gifted to a Black-led stewardship collective — was the perfect background to imagine what such alchemy could look like with our work: how do we take these institutions of harm and violence and redesign them to serve purposes of healing and regeneration.

On those same lines, while planning our travel routes from Atlanta to Pineview we realized the need to carpool for safety, because driving alone through central Georgia is still a risk for Black people and immigrants of color. With that realization, we contemplated the reasons and meaning of our work, to preserve and repair Black and brown spaces and seed structures for people to thrive outside the confines and threats of structural racism. In many ways, the landscape was a cathartic one — we safely enjoyed moments of peace, focus and joy in a rurality that has in large part been rendered threatening

Besides our company goals and strategic planning, we talked about our own personal hopes, goals, and fears. We dreamed about how our wildest dreams could inform the work we do and vice-versa. We listened to and affirmed each other. And we shared personal and precious dreams that have absolutely nothing to do with work, too. .

our approach to community development

Traditional community development models have often focused on outputs — affordable housing units, livable wage jobs, etc. — rather than lasting social outcomes. In order to transform existing conditions and enable social change to occur, we understand that the work of community organizing and movement building has to go alongside development work.

Leaning into organizing and movement building principles, we work with residents and community-based organizations in the neighborhoods we work in to lean into processes of co-creation.

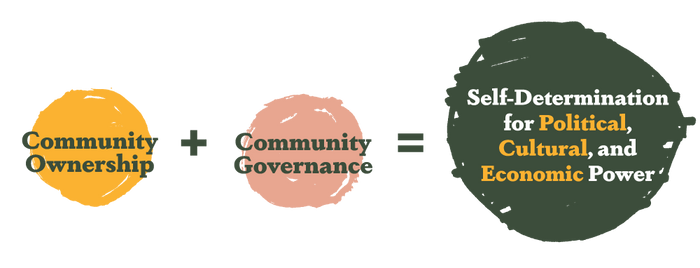

building models for community ownership and democratic control

Our work is rooted in principles of Restorative Economics, as developed by Nwamaka Agbo

Restorative Economics seeks to address a history of harmful economic practices. Property ownership in the US is rooted in racist exclusion and exploitation. Numerous actions of public and private actors ranging from the theft of Indigenous peoples' lands, slavery, racist housing covenants, to urban renewal and redlining are all vestiges of a system that has produced major inequalities. The racial wealth gap, disproportionately high poverty, and gaps in access to credit experienced by Black people are all rooted in unequal access to ownership.

Community ownership involves collective effort to control local assets and creates a pathway for low-income communities and people of color to expand power and generate wealth. Community ownership emerges as a direct response to the racist and capitalist notion of ownership. Black people and other economically marginalized communities historically developed numerous models of collective ownership including the Community Land Trust, cooperatives, mutual aid networks, and credit unions.

The Guild drew on this history in conceiving a model we're calling the Community Stewardship Trust (CST). Our aim with the CST is three-fold:

- To take properties (especially in majority Black neighborhoods) off the speculative market and into the hands of resident ownership

- To create an accessible investment product that transfers any financial benefit from development and reinvestment into the hands of residents — with a priority on legacy Black residents that have built the cultural fabric of these neighborhoods in the first place

- To create a vehicle for collective governance — CST members get to decide what goes into the properties we co-develop

Towards the end of 2020, we closed on a 7000 sq. ft. abandoned commercial property in the Capitol View neighborhood in Atlanta, with the goal of turning it into Atlanta's first community-owned and community-controlled mixed-use building and testing out our Community Stewardship Trust model.

Our plans include 18 units of permanently affordable housing (through a housing cooperative) on top of a grocery store, small commercial kitchens, and a

co-working and community gathering space. Upon completion of construction, the building will move into

the CST and members in the zipcode can purchase of

the trust for as little as $10/share. Each member will receive a vote, and net profits from the property get shared back

as community dividends. Details for the pilot can be

found at our websites.

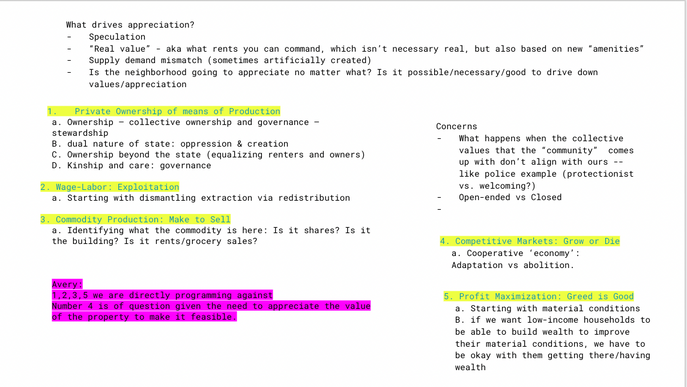

toward 'non-reformist reforms': building true alternatives to the status quo

Towards the end of 2020, when we closed on the first pilot property for community-ownership (918 Dill Ave.), we sought to explore what a non-reformist approach to our work could look like. A non-reformist, otherwise known as abolitionist reform, anti-capitalist reform, or transformative reform, works to threaten and weaken the status quo, while reformist reforms on the other hand tend to strengthen and maintain the status quo. The overwhelming majority of community development projects, even affordable housing projects, tend to be reformist in nature, and ultimately end up perpetuating the same inequities since they tend to take on a market-based approach, and don't grapple with the ways the 'market' in and of itself is the driver of those inequities.

We hold non-reformist reforms as a means to a more just, transformative and liberatory end. Real estate as an industry has its roots in colonization, slavery, and the perpetuation of violent acts through redlining, urban renewal, and present day gentrification and displacement of Black and other communities of color. Real estate has also always worked in conjunction with other oppressive institutions (such as policing) to preserve and grow property values. Further, finance as an industry overall, often in conjunction with federal, state and local policy, has played a role in the extraction of wealth from Black and Indigenous communities especially.

Non-reformist reforms are “conceived, not in terms of what is possible within the framework of a given system and administration, but in view of what should be made possible in terms of human needs and demands”

Image of the high-level draft of the analysis we conducted

Building alternatives that threaten or weaken the foundations of these industries is a tall task, and the work of lifetimes. But we've made the commitment to be bold, expansive and honest with our work and in 2021, we worked with Abolitionist Designer & Consultant Miliaku Nwabueze (more about her below) to conduct an analysis on what aspects of our work could push for non-reformist reforms, and what parts were inadvertently reformist.

A big takeaway for us was to continue to stay grounded in and move in solidarity with social movements — from the movement for Black liberation, to housing justice and social housing movements. We're working on sharing the rest of our learnings over the course of this year.

miliaku nwabueze (she/her)

Abolitionist designer

Miliaku is currently completing her MFA in Transdisciplinary Design at Parsons at The New School. Her experience with working humans spans across corporate america, non-profits, grassroots organizations, cooperatives, and a multitude of different projects and initiatives. She has familiarity with software design, transition design, finance, pedagogical and curriculum development, and project management. In her work, she has witnessed the potential of relationships to maintain the status quo and to subvert it. In building consciousness around her blackness and queerness, she has developed tools and frameworks she hopes will help us deviate from reformist patterns and enter generative relationships with each other and all earthlings. As a staunch abolitionist, she believes in rethinking everything and incorporates design methodologies into (un)making.

updates from our Pilot community-owned project at 918 dill ave

Evolving from our 2020 Transformative Development Cohort, The Guild has developed a long-standing and significant relationship with Urban Oasis Development. Led by Joel Dixon and Wole Oyenuga-Sims, Urban Oasis are our co-developers on our pilot project at Dill Ave, and have been invaluable partners and stewards as we’ve navigated the complexities embodied in this work. Urban Oasis has been working to provide permanently affordable housing in Atlanta in partnership with the Atlanta Land Trust, and are actively engaged in the neighborhoods within which we are working. Whether through weekly check-ins or issue-specific deep-dives, Joel and Wole have provided counsel and feedback as we’ve engaged with the neighborhood’s residents, collated financing, worked through permitting issues, and moved forward towards construction. We look forward to partnering with Urban Oasis for years to come!

commercial programming

We began the year already having heard from the residents of Capitol View that the site and the surrounding neighborhood struggles with access to healthy food options due to food apartheid; there are no grocery stores offering fresh produce in the vicinity. Consequently, we began conversation with Leaven Kitchen, in order to engage them to operate a small format grocery store with 3 small commercial kitchens. Leaven is a Black woman-owned collaborative kitchen that aims to serve emerging food entrepreneurs.

The grocery store will also help cement the building in the routine lives of the residents of the surrounding neighborhoods. In the course of our conversions with Leaven and the neighborhood, we added the intent to include 3 small Department of Health certified kitchens which would serve hot food through kitchen windows opening into the grocery space. As these conversations developed, we thought through how the remaining commercial space could meet the needs of the neighborhood and BIPOC tenants, arriving finally at the concept of a co-working space that could host events as well as smaller format programming. Additionally, we held several meetings with Capitol View residents to share our plans for the residential floors. We presented the design options that best fit the site conditions with an eye towards construction methodology, and incorporated feedback on the layout of the apartments.

residential programming

To break away from the isolated typology of the elevator-corridor-apartment trajectory that is common to most apartment buildings, the residents of the building are provided with an open porch on both residential levels. This not only provides access to the apartments once the residents disembark from the elevator or travel up the open stairwells, but is also a large informal space that the residents can occupy in any way over the course of the day. Such spaces bring our domesticities in conversation with the domesticities of others, while allowing for retreat into our private spaces upon exhaustion of the social muscle. They are spaces of solidarity that reflect all our labor.

"Moments of spontaneous interaction help us weave our rituals of care into collective action... and engender a sense of community built on shared daily experiences."

Moments of spontaneous interaction — a conversation over a morning cup of coffee, or while watering plants, or taking out the trash — help us weave our rituals of care into collective action, and engender a sense of community built on shared daily experiences. At this juncture in the planning process, this shared open space also became a way of satisfying the City’s requirement for open space on site while freeing up the ground plane for parking spaces for which the neighborhood’s residents advocated, to alleviate the increasing demands on street parking capacity around the project. Upon having navigated all these challenges, we received our planning permit at the end of July and began the process of working on our building permit application

Relational Design & Co-Creation

Central to our approach to development is designing with, not for communities. Staying true to this ethos, we continued work on our 918 Dill Ave. pilot with community design sessions and limited in-person imaginings.

We led design sessions with residents and key stakeholders in the neighborhood to understand their needs and priorities, as well as get feedback on the community ownership and collective governance model (the Community Stewardship Trust) that we developed.

Resident feedback went directly into our plans that we then filed with the city. We also got feedback on our governance structure that we're incorporating into the CST in 2022.

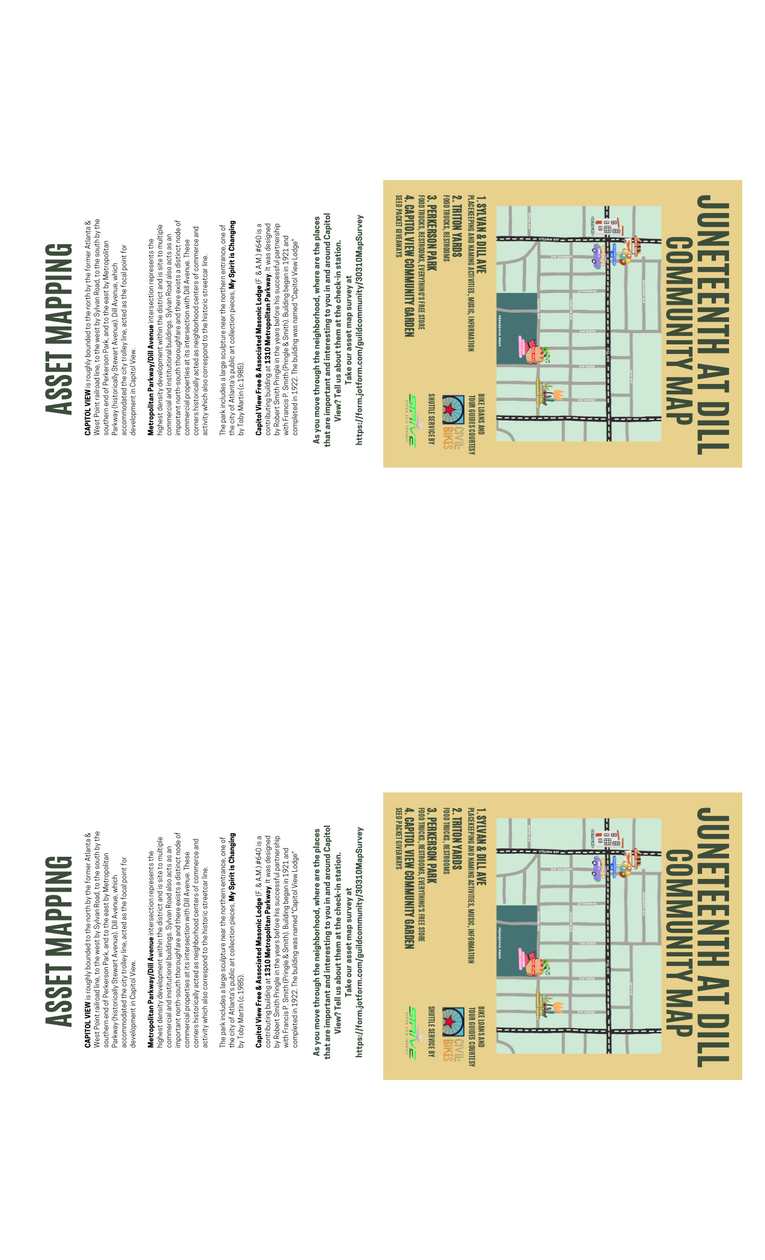

We officially "opened" Dill Ave. and its adjacent open lot in a community Juneteenth celebration that spanned multiple sites in Capitol View. Murals on the building's exterior and live "drawing boards" on the lot invited neighborhood residents to dream of what they would like to see there and do some community asset mapping.

This became as much future dreaming as

it was discovery of what and whom

Capitol View already contains.

Screen-sharing via Zoom enabled us to vision feedback in real time as we discussed apartment interiors and parking solutions, weighing resident needs and conveniences with community concerns.

Public feedback came full circle as these sessions became opportunities to educate the community on the various zoning regulations at play

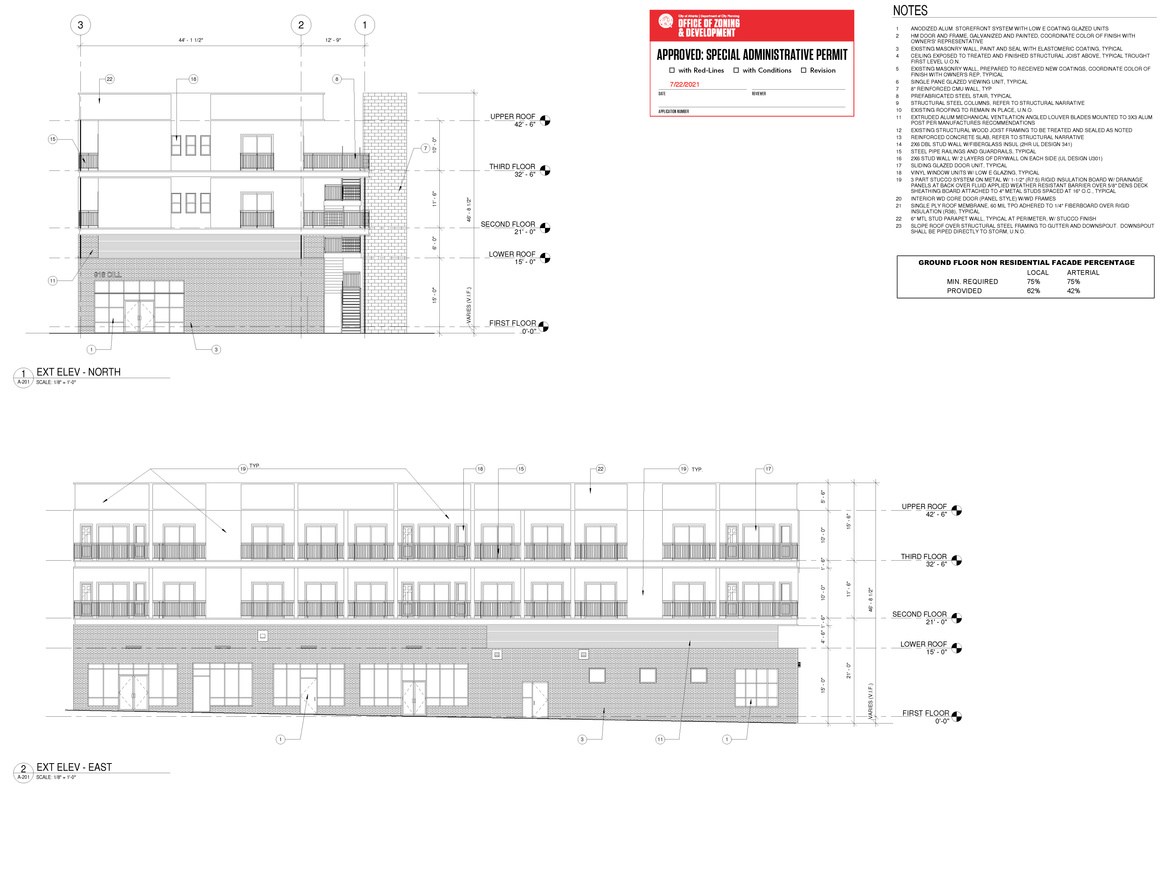

updates on planning and building permits

As we worked through the schematic design for the building, we began the various processes relating to the planning permit for the project. The project required a variance, as the site’s topography caused us to breach the height limit by several feet. The variance process involved various meetings with the residents of Capitol View as well as a vote by the Neighborhood Planning Unit, culminating in an Approval by the Zoning Review Board. The variance approval cleared the way for us to proceed with our full planning permit application. As we are in Atlanta’s Beltline Overlay District, we had to present our project for approval to the Beltline Design Review Committee, and comply with the various development controls, use and affordability requirements for mixed-use projects located within a half mile of the Beltline.

The simultaneous process of satisfying these regulatory requirements while also incorporating the desires of the neighborhood’s residents re-affirmed our conceptual design.

our approach to architechture

Typical development embodies finance's desire to reproduce safe havens for investment returns, rather than safe havens for people. This desire translates into pre-approved typologies of buildings that are viewed as safe "products" for development to reproduce. That the same very-large multifamily building, or residential subdivision, or cluster of town-homes is being built all over the country is an illustration of the homogenization of our built environment at the behest of Capital. This ‘product delivery’ approach to architecture is based on viewing renters as being interchangeable – one qualified renter is as good as another. People everywhere are viewed as having the same preferences, with the only characteristic deemed worthy of note being their income level.

Working as complicit service provider, architects aid this homogenization by focusing solely on presenting gimmicky building facades that are thought to appeal to renters and buyers, while relinquishing all other considerations of space and human interaction to Real Estate.

"In our view, a building exists to stabilize the lives of its inhabitants within the context of their social relationships, and architecture should facilitate the network of social relationships within which we live."

Architecture now presents a de-facto design based in these development driven logics; less a matter of nuanced spatial thought, and more a shopping-cart assemblage of those products and processes which result in prescriptive buildings. Unable or unwilling to confront this stale paradigm, the Architect is increasingly relegated to project managing these autonomous technocratic processes of industry. As the construction industry’s various processes have been configured to produce material at scale for such volume-oriented homogenous development, the more we build of those typologies, the more “inefficient” it becomes to build anything else.

Innovations such as pre-fabricated or factory-built housing trumpet supply-side solution-ism to the housing crisis, even as they exacerbate the loss of artisan skill, while our homes and apartments become ever more standardized. Insurance as an industry is also complicit. It values those developments higher which are built of ever more engineered, inert materials that sell nostalgia, built in plastic: the American dream, now in Poly-Vinyl Chloride.

In 2021, The Guild confronted these various financial, physical, and regulatory pressures to begin to build a place built on cooperation. A building serves to stabilize the lives of its inhabitants within the context of their social relationships, and Architecture should be the act of facilitating the network of social relationships within which we live, along with our corresponding notions of care and risk.

our technical learnings from working on an adaptive reuse project

Dealing with an old building is both enchanting and frustrating. The existing building was built in 1930 and is a combination of structural masonry and wood, with steel reinforcements being added over the years. The building is currently divided into six retail suites, in varying states of disrepair. The process of putting the building permit together first required documenting the existing conditions, a task made harder by the building’s age. Once the existing conditions had been drawn, we worked for several months with various consultants to draw the construction drawings in detail. This is always an iterative process, requiring constant coordination between the disciplines in order to make sure that all the systems come together.

This task is made harder when dealing with existing conditions. To make room for the co-working space on the ground floor, we intend to demolish portions of the interior demising walls. This will unite four existing narrow suites into one, thus providing a large flexible space for events when necessary. In accordance with the Structural engineer’s guidance, we modified our schematic plans to conform with the remaining portions of the existing walls to reduce the overall need for steel reinforcement. Concurrently, we reconciled the location of the new structural columns which will support the proposed residential floors above. Coordinating the location of the old and new structural elements, while incorporating lateral bracing required a nimble dexterity on the part of our engineers.

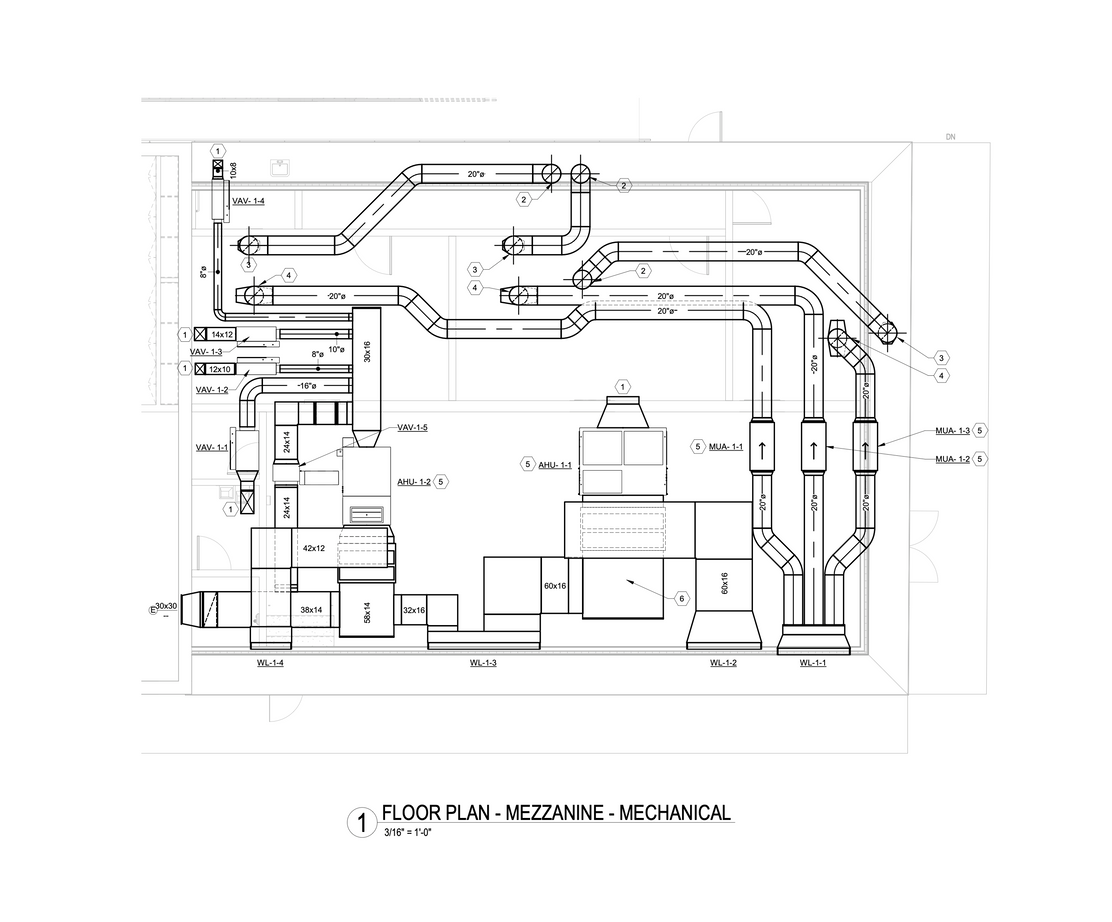

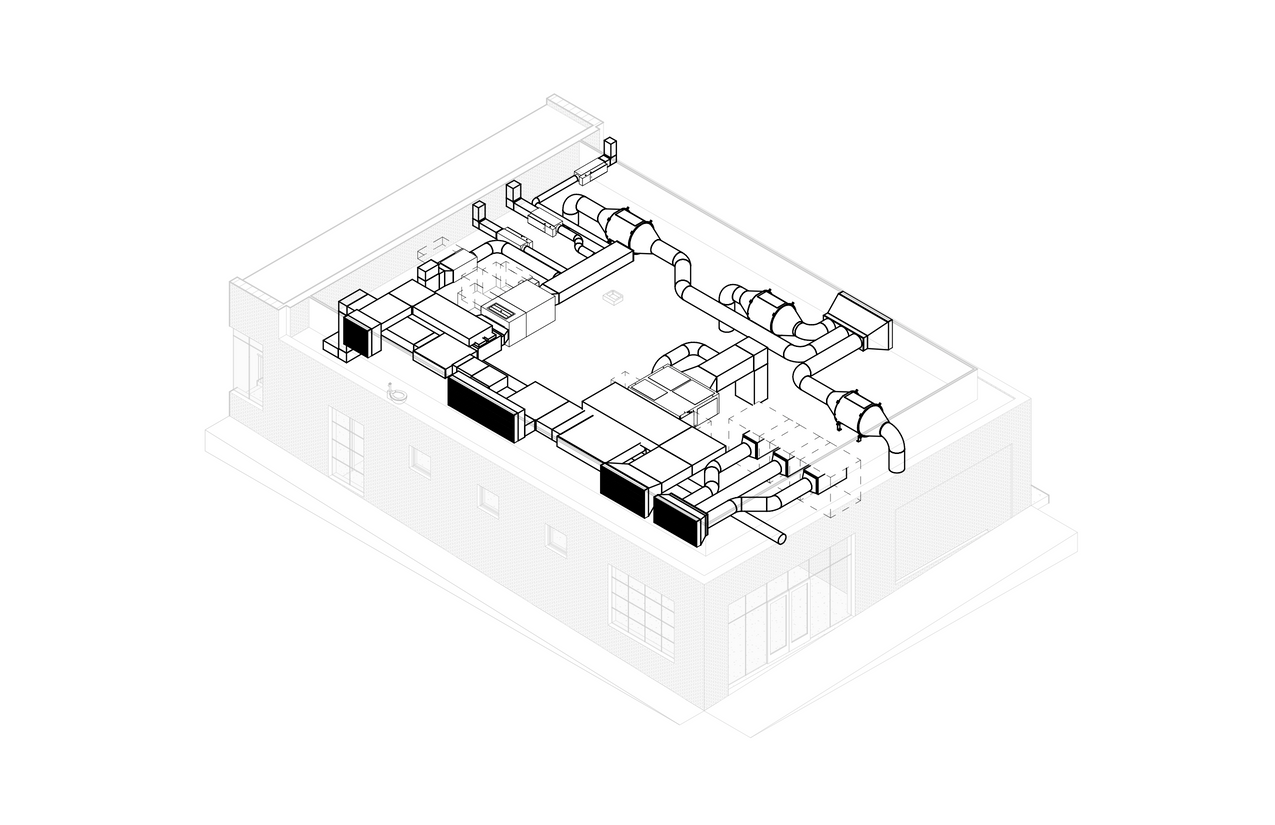

Locating the Mechanical systems for the various uses of the building proved to be another challenge. The department of health certified kitchens require a tremendous amount of mechanical equipment to function, all of which would need to be located somewhere. Here the variable height of the existing building and the site’s topography proved useful. Since the new residential floors will be built above the highest point of the existing building, and as the existing building steps up past the suites that will eventually house the kitchens and the grocery, we were able to fit most of the Mechanical equipment in in a mechanical mezzanine above these suites, but below the new composite concrete and metal slab that will form the fire-rated barrier between the residential use above, and the commercial spaces below. Further, upon investigation we found that there was enough room between the roof of the existing building and the new slab above that we could also fit most of the heating, ventilation and cooling equipment for the co-working space in this mechanical mezzanine. This meant that we would not have to effectively reduce the existing ceiling heights by having mechanical equipment suspended in the spaces themselves. This ceiling height is precious especially since we’ve already had to reduce it by a few feet: as the building steps up across the site, uniting the four existing suites below by demolishing portions of the demising walls also meant having to reconcile the varying floor levels by pouring new concrete slabs such that all of the floor remains level and accessible. Since the ceiling heights remain fixed, this lowered the ceiling height in one portion of the space.

Drawing the residential floors was easier only insofar as we did not have to deal with existing conditions. Adhering to the footprint of the existing building below, the residential floors above are an exercise in the consolidation of services, to maximize living space. Grouping plumbing walls for kitchens and bathrooms limits the number of plumbing chases in the building while also providing a consolidated zone in each apartment for mechanical equipment to be deployed. Consequently, we are able to maintain 10’ ceilings in all spaces except for the bathrooms, where ceilings are reduced to the more conventional 8’. The 10’ ceiling heights in the living spaces make the apartments feel larger, while also allowing in more light.

After working on the construction drawings for most of the fall, we submitted the complete building permit application in January 2022.

sharing our praxis and learnings with academia

Emmanuel admassu (he/him)

Founding Principal, AD-WO

Professor, Columbia University

Over the course of the fall, The Guild engaged with student work in an Urban Design studio led by Architect Emmanuel Admassu at Columbia University. He and his team challenged the students to think about the possibility of Architecture and Urbanism freed from the regime of property. They selected numerous sites within Metro Atlanta to posit solutions rooted in the ethos of cooperative ownership and land liberation, and built on communality and solidarity instead of capitalist hegemony. We presented our model to the students along with the challenges we've encountered and the solutions we've developed to various issues. Additionally, we provided feedback as they developed their projects.

As Architecture and Urban Design increasingly give over to the momentum and desires of Capital, the work that Architects such as Emmanuel are doing to engage these vectors in Academia becomes ever more urgent.

DR. Elora L. RAYMOND (she/her)

Assistant Professor, Georgia Tech

Early in the year The Guild engaged with student work in a City Planning class at Georgia Tech led by Urban Planner and Professor Elora Raymond. The course work was informed by her prolific scholarship on issues pertaining to the financialization of housing and land, and concomitant issues of housing justice and inequity. The students engaged with our project at Dill Avenue in the form of the course’s culminating case study. They were encouraged to wrestle with the tensions inherent in a project which is attempting to reconcile permanent affordability with the goal of building community wealth for those legacy neighborhood residents who have long been locked out of wealth building opportunities and participation in their own neighborhoods. The Guild provided feedback as the students engaged with the various financial dynamics, and presented solutions they felt best represented the aspirations of the project. Elora’s work with students in the Planning and Development departments at Georgia Tech continues to provide them with an invaluable critique of our financialized housing systems.

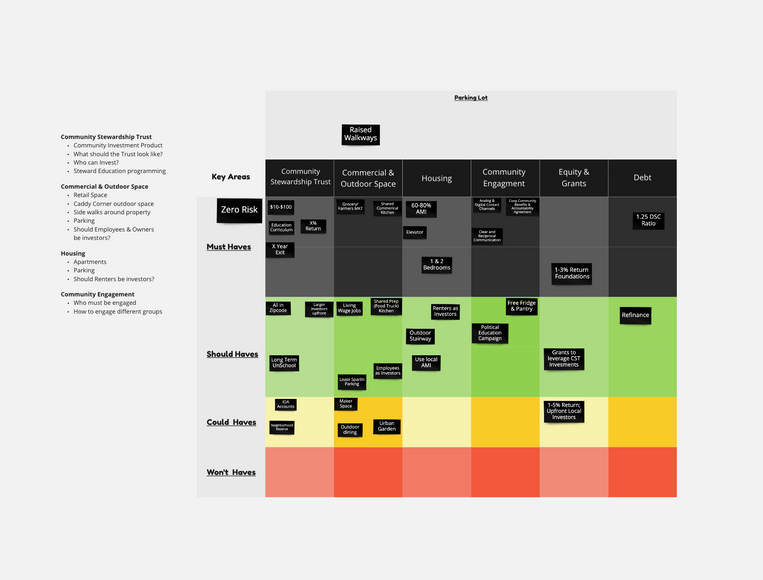

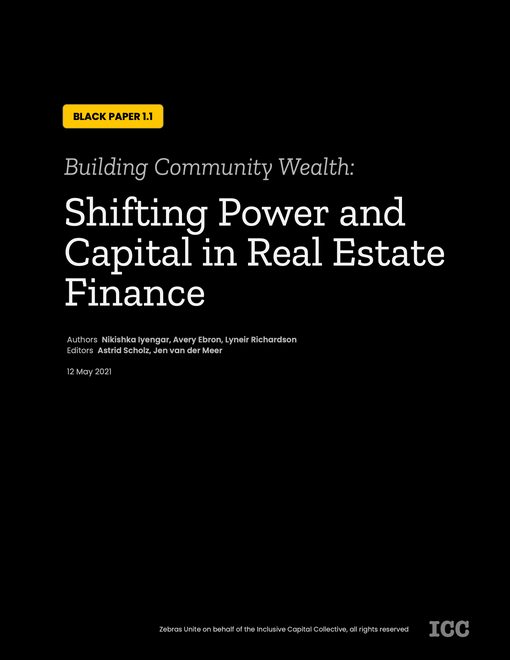

designing an equitable capital stack

Potential risk & return

common equity

Preferred equity

mezzanine debt

senior debT

Typical capital stack

In a typical capital stack for a real estate project, the senior debt (provided by banks or CDFIs) takes on the least amount of risk, since the debt is collateralized by the building, and has relatively low returns. The equity, coming from a developer or investor/investment group, tends to take on the most risk and receives the highest returns.

community equity

Low risk, highest % of returns

solidarity equity: REF

High risk, lowest % of returns

mezzanine debt: invest atlanta

Low risk, lowest % of returns

senior debt: lisc

Lowest risk, low % of returns

the guild's capital stack

In trying to repair some of the historic inequities that have occured around real estate, housing and land theft, we understand that this risk-return paradigm is fundamentally flawed. It doesn't take into account the risk Black and brown communities bear due to systemic racism — the risk, for example, that they will be displaced when development happens in their neighborhood. Our capital stack aims to flip that script — we partner with philanthropy and values-aligned wealth holders who are committed to sacrificing financial returns in service of holistic community development and ultimately, community

self-determination. In our pilot, this critical partner was Kataly Foundation, and more about how we engaged philanthropy can be found below.

how we engage philanthropy

Finance has long acted as a tool to extract wealth from communities of color, and the financialization of housing is at the core of the housing crisis we're seeing unfold everywhere today. Utilizing the tools of capitalism to reinvent a more equitable economy is challenging work. The Guild works to link Black and Brown communities to non-extractive capital sources that ultimately help shift power from wealth holders to communities. The models we're engaged in serve to prevent displacement, to build intergenerational wealth, and remedy longstanding histories of redlining and disinvestment.

Philanthropic partners are an important resources to help invest in and bring to scale such models that do not currently pencil using traditional tools of finance.

trust-based philanthropy

At its core, trust-based philanthropy is about reversing the inherent power in funder-grantee relationships, and shifting power away from foundations and capital holders toward marginalized communities. As abolitionist scholar Dr. Ruth Wilson Gilmore names, philanthropy is wealth that is twice-stolen — the first time when wealth is accumulated through extraction of unpaid or underpaid labor and land, and the second time when that wealth avoids taxation through philanthropic vehicles. Our engagement with funders begins with this critical truth. Our two largest funders — the Kataly Foundation and the Kendeda Fund are both institutions that are spending down the wealth accumulated towards supporting community ownership models in communities of color. Rather than just a funder, Kataly Foundation has shown up as a partner in our work, learning as much from us as we are from them. Details about our partnership, including numbers and what trust-based philanthropy looks and feels like can be found here.

The Guild's work seeks to push philanthropic funders to think of scale not simply in terms of a number of housing units delivered or households served, but in terms of how well we've scaled transformation of whole systems and ways of doing. Our partnership with the Kataly Foundation is helping to incubate new financial tools and resources to enable equitable and community-owned developments in Atlanta.

project financing updates

Our project was not exempt from the effects of the pandemic on development funding and nationwide escalation in construction prices. While negotiating the various requirements for the planning permit, we were struck by lenders’ reluctance to underwrite any commercial space — the pandemic made them wary of financing space that relied on in-person retail activity. But housing is not an isolated good. Resilient communities are built with and around commercial spaces that provide care, nourishment, resources, entertainment and meet proximal needs. Through much of the summer we sought the right construction lender, to ensure that we would be able to build the grocery store and other commercial space we had been discussing for the project. We finally engaged with LISC, our construction debt lender, and a HUD-insured permanent mortgage program specifically meant for Cooperatives. This resulted in the lowest long-term interest rate we could secure for the project while ensuring that the residents of the building would have representation within the larger Stewardship trust proportional to their interest in the management of the project.

Even as we secured a construction commitment, our construction costs rose by nearly a million dollars without change in the design of the project. As the project’s financing is tied to the rental revenue of the project, the affordable rents could not support adding a million dollars to the senior debt. We pursued an application to Invest Atlanta’s Housing Bond funding program for small multifamily developments. In accordance with the program’s guidelines, we will be securing enough long-term subordinate debt to ameliorate the increase in construction costs without needing to increase rents.

In November we closed on equity for the project with REF. Truly catalytic, closing on this capital early allows us to start the process of fabrication of materials for the project. Given the attenuated nature of supply chains, with lead times on Steel and Wood reaching 18 - 26 weeks respectively, and when quotes on materials are only being honored for 10 days, having capital in-hand to execute as soon as our Building Permit is approved will ensure that we can hit the ground running.

growing the ecosystem to shift power in real estate finance

The Guild joined the Inclusive Capital Collective as an early member to help create a pool of capital dedicated to BIPOC developers doing transformative real estate projects in their communities

Avery and Nikishka along with ICC member Lyneir Richardson authored a Black Paper titled Building Community Wealth: Shifting Power and Capital in Real Estate Finance. Our goals for the paper were to raise awareness and resources to address the capital, policy, and operational needs of BIPOC developers, and to highlight the critical, groundbreaking work they have and continue to do in the most marginalized communities. We also wanted to push funders — from philanthropy to CDFIs and banks — to rethink the terms of their investments to move beyond DEI goals, towards structures and models that facilitate community ownership and self-determination.

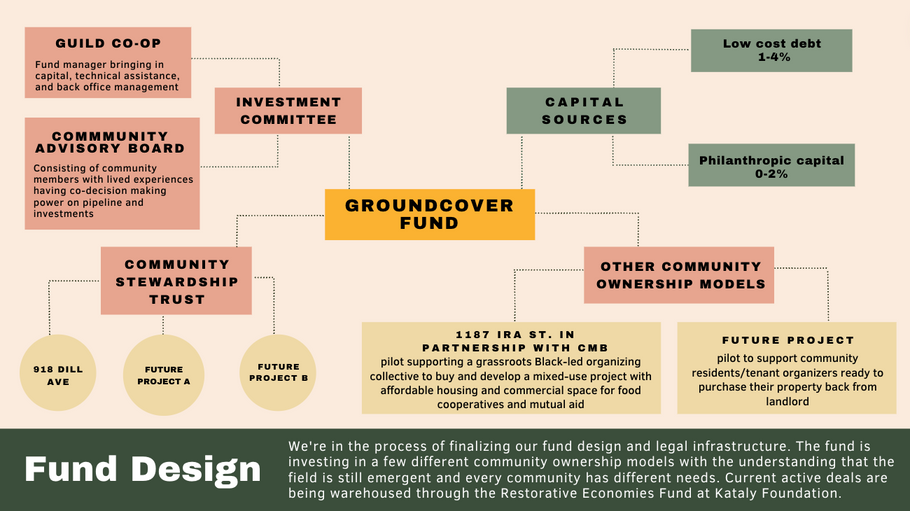

GROUNDCOVER: our fund to scale community ownership of real estate

The Guild's journey from co-living to development was borne from our experiences in creating spaces for social transformation. Even while working with a mission aligned developer to create flexible, affordable housing and co-living space, we realized that the levers of limitation find their fulcrum in the genesis of a project. Where, how and from whom is the capital stack derived? Who is at the table as the project is conceived? In attempting to build community, who's spoken with the community that was there already? What are they saying? What does it mean, what can it look like, for people to have the tools they need to build communities for themselves?

Groundcover is the embodiment of our thesis that housing should and can be a human right, rather than a commodity. By acquiring and removing property from the speculative market and putting it into the collectively governing hands of the communities in which it exists, we can start to see the extractive nature of the real estate industry reverse course to a tool of empowerment and collective, rather than individually-centered, wealth building. Groundcover develops properties on behalf of communities and community-based organizations, providing funding and technical assistance to those aims. 918 Dill Ave, in Atlanta's Capitol View neighborhood, is our first pilot under the initiative.

groundcover's second pilot investment

As we build out our integrated capital fund to seed community-owned and community-controlled models of real estate, we have been working on pilot deployments to test our investment thesis. Below is a very rough draft of how we're designing our fund. We're sharing this unfinished version as part of our commitment of learning and growing in public, with the goal of being transparent, and demystifying finance and real estate development along the way. Given that, please note it is not final and can evolve.

As seen in this diagram, we are investing in community-ownership models broadly — while we have developed and are testing our model of a Community Stewardship Trust, we also don't want to be prescriptive at this stage. So much of this work involves experimentation with integrity.

Given that, we invest in both real estate that will go into CSTs, as well as other projects that take on other community ownership models — from cooperatives to land trusts.

Our second investment is to build a mixed-use project with COMMUNITY MOVEMENT BUILDERS (CMB) that will include both deeply affordable housing as well as commercial space for their food cooperatives, youth development and mutual aid programs. CMB is a member-based collective of black people building sustainable, self-determining communities through cooperative economic platforms and collective community organizing. The Guild is acting as development partner on the project and our Groundcover fund is providing equity capital for the project as well. Investing in grassroots Black-led development like this project is critical to our mission.

programming updates

In the Black neighborhoods adjacent to our pilot at 918 Dill Avenue, over 5,000 residents and 270 small businesses in the area face significant displacement risk.

At The Guild, we envision the Community Stewardship Trust (CST) not only as a community wealth building entity, but also a vehicle for local capacity building. With the support of the CST, community engagement can be ongoing and intentional, rather than sporadic and transactional. Vacant, underutilized, or newly available properties can be collectively queued, approved, and advocated for by local residents, so that community assets of the highest priority are delivered. To support local residents and organizations to learn more and get involved in their community’s development, in 2022 we’re launching capacity building programming in partnership with the Capitol View Neighborhood Association (CVNA), Incremental Development Alliance, and other community partners. The programs will provide free, hands-on programs and resources that support neighborhood residents, businesses, and organizations to build, own, and collectively govern local real estate. This will include financial literacy/ investor education, stewardship education, political education, and professionally-led real estate development training. The courses will help build community wealth and power by democratizing the often gatekept knowledge and development in the real estate industry.

We shifted our Community Wealth Building Accelerator in 2021 to align more closely with our work to build models for community ownership of assets overall — both real estate and businesses. With financial assistance from LISC and Kiva, in partnership with The Kenekt, we developed a series of compensated surveys and interactive small group interviews for local Black entrepreneurs to directly speak to their needs. From this feedback, we are building a digital hub to directly resource business owners with operational and financial support. This macro-level work with local businesses allows our team more capacity to focus on the systemic issues and dig more deeply into Atlanta's existing ecosystems of entrepreneurial support, digging into the areas where we differentiate.

We also worked with graduate students and the Capitol View community to develop an interactive Community Asset Map that empowers local residents in local governance decisions that will be rolled out later this year.

our role in the ecosystem & movement solidarity

Looking back....

2021 was definitely a period of transformation for us, and it involved living into one of our core values of moving at the speed of trust. To that end, we also wanted to honor the work that other Black and POC-led collectives have been doing in Atlanta towards the same goal of building a 'solidarity economy', and see how we could either build new partnerships and collaborations, or deepen existing ones.

We worked with organizer and consultant Avery Jackson through their firm Wild Talk to develop a process and container for reflection and feedback conversations with other groups. Through these sessions, we learned of better ways to practice solidarity and collectively help grow the ecosystem.

avery jackson (they/them)

Principal & Founder, Wild Talk Stories & Strategies

To look forward...

Addressing the challenges facing Black and brown communities in Atlanta — from wealth and income inequality, displacement and gentrification, to disparities in access to health care and healthy food — requires an ecosystem approach. In our commitment to addressing inequities around land, housing and ownership of assets, The Guild is working to build and strengthen a local solidarity economy — bringing our experience with finance, development, and community organizing and working with other partners to create a new economic reality for Black communities.

Building on this ecosystem and place-based approach, The Guild is launching the Atlanta Peoples Land and Housing Alliance (PLHA) in 2022 to convene various players to advance policies that bolster public support for affordable and social housing, community ownership, tenant rights, and public funding that prioritizes extremely low-income communities and residents

As more community development and housing justice groups are brought together, each of us sharing our challenges, working cooperatively on solutions, and building local political power together, we envision being able to build a just and liberatory future for all Atlantans.

As more community and housing justice groups are brought together, each of us sharing our challenges, working cooperatively on solutions, and building local political power, we envision being able to transform the status quo towards a more just and liberatory future for all Atlantans. The Guild is currently providing ongoing political education and real estate & finance programming, and we plan to leverage our ecosystem partnerships to support the community organizing for affordable housing and community ownership initiatives.

The Guild’s PLHA project draws from work our Organizing Director Zach Murray started in Oakland, CA to provide a practical model for organizing local residents (prioritizing Black legacy residents), community-based organizations, and capital in the effort to take real estate off the speculative market, and into permanent community ownership. Through continuing this work in Atlanta, we aim to do the same and also support capacity and power building for Black communities, so we can push for solutions within Atlanta's Neighborhood Planning Units, Invest Atlanta, Atlanta Housing Authority, and other public institutions.

Ultimately, all of our work wrestles with and balances the tension between community wealth building, permanent affordability (both for housing and community amenities), and capacity building for historically and currently marginalized communities. We also hold the tension between working within the confines of the existing system(s), while building towards alternative ones. Our core goal in expanding our role in organizing and movement building is to be able to hold and balance these tensions with integrity, and in solidarity with the people most impacted by them.

Press & other media

Seth Berkman, New York Times, 11/23/2021

Dean Boerner, Whatnow Atlanta, 3/16/2021

John Ruch, Saporta Report, 6/12/2021

Steve Dubb, Nonprofit Quarterly.org, 7/28/2021

Nikishka Iyengar, Avery Ebron, Lyneir Richardson, Inclusive Capital Black Paper

Common Future, 9/30/2021

fellowships

We joined 11 other emerging place-based funds from around the country that are aiming to close the racial wealth gap in their communities, and learned how to raise capital, legally structure the fund and and design terms to deploy the capital that was aligned with our values and mission.

We were selected for Purpose Foundation's fellowship on Shared Ownership. Through this fellowship, we receive technical assistance to continue building out Groundcover's fund.

Common Future Bridge Fellows

Our Ecosystem Director Nikishka Iyengar was selected as one of eight fellows bringing Community-Centered Solutions to the Forefront in the South

We joined the Inclusive Capital Collective to help shift the funding ecosystem nationally and push for more community-owned models

We were selected as an innovator in the Ashoka x Brookings Institution Challenge on building new economic architecture that closes the valuation gap for Black homes and real estate

We participated in the development of a toolkit and strategy to help combat displacement